Dictionaries and dataframes#

Needing a better way of ordering dictionaries was one of the original inspirations for Sciris back in 2014. In those dark days of Python <=3.6, dictionaries were unordered, which meant that dict.keys() could give you anything. (And you still can’t do dict.keys()[0], much less dict[0]). This tutorial describes Sciris’ ordered dict, the odict, its close cousin the objdict, and its pandas-powered pseudorelative, the dataframe.

Click here to open an interactive version of this notebook.

The odict#

In basically every situation except one, an odict can be used like a dict. (Since this is a tutorial, see if you can intuit what that one situation is!) For example, creating an odictworks just like creating a regular dict:

[1]:

import sciris as sc

od = sc.odict(a=['some', 'strings'], b=[1,2,3])

print(od)

#0: 'a': ['some', 'strings']

#1: 'b': [1, 2, 3]

Okay, it doesn’t exactly look like a dict, but it is one:

[2]:

print(f'Keys: {od.keys()}')

print(f'Values: {od.values()}')

print(f'Items: {od.items()}')

Keys: ['a', 'b']

Values: [['some', 'strings'], [1, 2, 3]]

Items: [('a', ['some', 'strings']), ('b', [1, 2, 3])]

Looks pretty much the same as a regular dict, except that od.keys() returns a regular list (so, yes, you can do od.keys()[0]). But, you can do things you can’t do with a regular dict, such as:

[3]:

for i,k,v in od.enumitems():

print(f'Item {i} is called {k} and has value {v}')

Item 0 is called a and has value ['some', 'strings']

Item 1 is called b and has value [1, 2, 3]

We can, as you probably guessed, also retrieve items by index as well:

[4]:

print(od['a'])

print(od[0])

['some', 'strings']

['some', 'strings']

Remember the question about the situation where you wouldn’t use an odict? The answer is if your dict has integer keys, then although you still could use an odict, it’s probably best to use a regular dict. But even float keys are fine to use (if somewhat strange).

You might’ve noticed that the odict has more verbose output than a regular dict. This is because its primary purpose is as a high-level container for storing large(ish) objects.

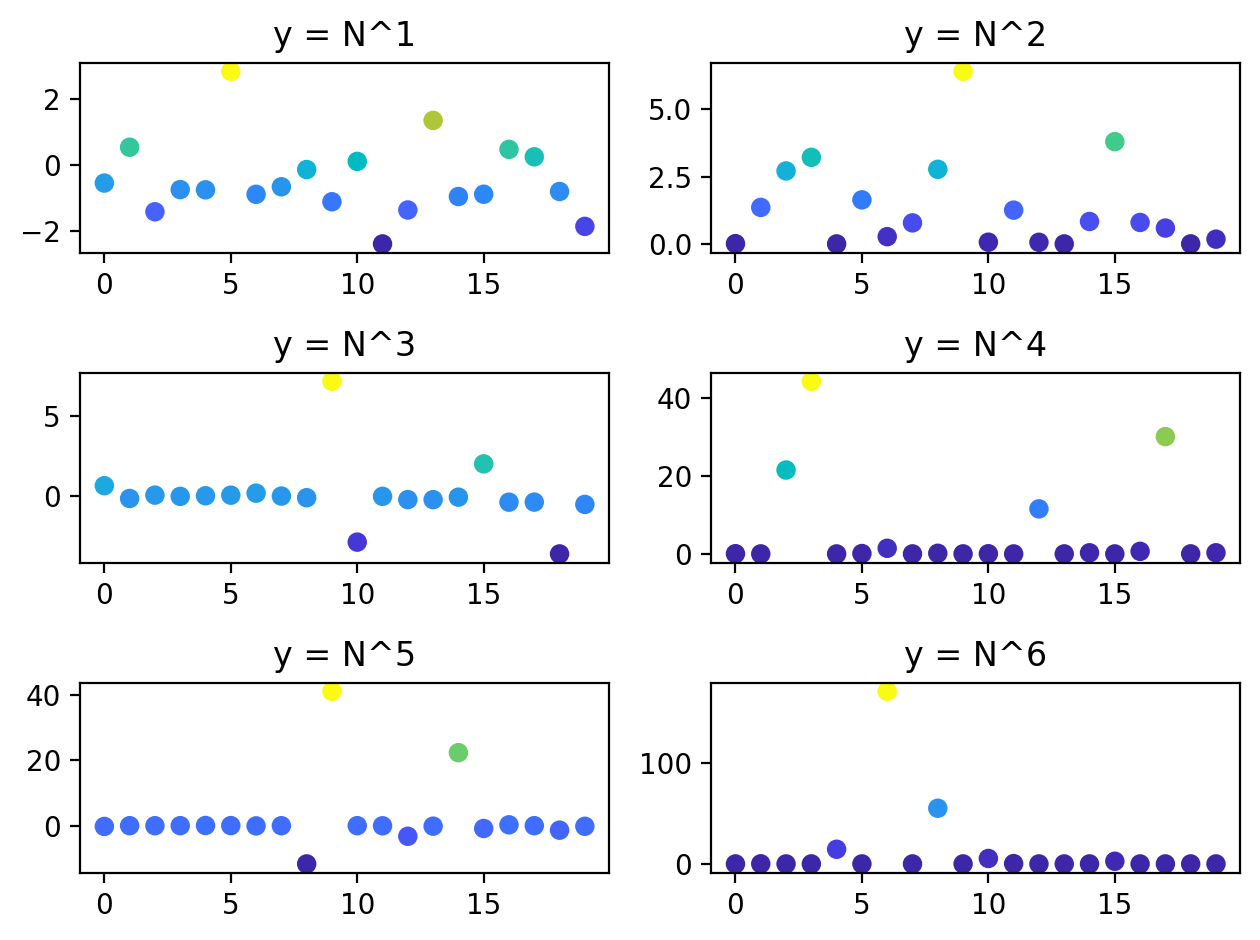

For example, let’s say we want to store a number of named simulation results. Look at how we’re able to leverage the odict in the loop that creates the plots

[5]:

import numpy as np

import pylab as pl

class Sim:

def __init__(self, n=20, n_factors=6):

self.results = sc.odict()

self.n = n

self.n_factors = n_factors

def run(self):

for i in range(self.n_factors):

label = f'y = N^{i+1}'

result = np.random.randn(self.n)**(i+1)

self.results[label] = result

def plot(self):

with sc.options.context(jupyter=True): # Jupyter-optimized plotting

pl.figure()

rows,cols = sc.getrowscols(len(self.results))

for i,label,result in self.results.enumitems(): # odict magic!

pl.subplot(rows, cols, i+1)

pl.scatter(np.arange(self.n), result, c=result, cmap='parula')

pl.title(label)

sc.figlayout() # Trim whitespace from the figure

sim = Sim()

sim.run()

sim.plot()

We can quickly access these results for exploratory data analysis without having to remember and type the labels explicitly:

[6]:

print('Sim results are')

print(sim.results)

print('The first set of results is')

print(sim.results[0])

print('The first set of results has median')

sc.printmedian(sim.results[0])

Sim results are

#0: 'y = N^1':

array([-0.54016972, 0.54049209, -1.40646494, -0.73719452, -0.74496715,

2.83032182, -0.87933836, -0.65211419, -0.13288216, -1.10391221,

0.11377512, -2.37603465, -1.35245841, 1.34875231, -0.94662911,

-0.87763284, 0.47554452, 0.25084 , -0.79472331, -1.84704125])

#1: 'y = N^2':

array([1.03262706e-02, 1.35456400e+00, 2.70620145e+00, 3.21129521e+00,

6.03875928e-04, 1.63405220e+00, 2.69367871e-01, 7.80657402e-01,

2.76728446e+00, 6.40165649e+00, 6.43326833e-02, 1.25308353e+00,

6.06377072e-02, 6.91062330e-06, 8.32721320e-01, 3.79333343e+00,

7.95878583e-01, 5.88378319e-01, 2.31384103e-03, 1.76826542e-01])

#2: 'y = N^3':

array([ 6.64836788e-01, -1.35990256e-01, 7.48025386e-02, -4.33966724e-03,

3.27891266e-02, 7.03836176e-02, 1.96451012e-01, 1.46180983e-02,

-8.81772149e-02, 7.20469112e+00, -2.87054190e+00, -2.11123473e-03,

-2.06484315e-01, -2.09488878e-01, -5.44535601e-02, 2.03248758e+00,

-3.66714552e-01, -3.63381686e-01, -3.60970122e+00, -5.08318972e-01])

#3: 'y = N^4':

array([5.74118981e-02, 1.05249326e-02, 2.15752454e+01, 4.43863464e+01,

1.12007956e-04, 1.00339723e-01, 1.45197533e+00, 1.14267287e-02,

1.63523380e-01, 1.42164766e-02, 4.75173627e-02, 9.86919645e-08,

1.15851385e+01, 9.84085292e-03, 2.91701735e-01, 7.35441544e-04,

6.61696371e-01, 3.01576269e+01, 1.68033509e-02, 2.98005002e-01])

#4: 'y = N^5':

array([-2.28533162e-01, 1.13613751e-05, -1.19251281e-02, 4.81322573e-03,

6.33689600e-02, 2.74856360e-02, -6.41970894e-02, -9.88575519e-03,

-1.17046666e+01, 4.11312024e+01, 4.52099821e-05, -3.29798655e-02,

-3.24457869e+00, -1.45264592e-01, 2.23440640e+01, -8.54890805e-01,

2.61914419e-01, 1.08767892e-03, -1.37680945e+00, -1.83465829e-01])

#5: 'y = N^6':

array([6.75146146e-05, 1.25063025e-01, 1.26266318e-04, 2.84635575e-02,

1.46171972e+01, 2.00562911e-02, 1.71858281e+02, 4.52896845e-03,

5.54399758e+01, 9.15985733e-10, 5.43303074e+00, 2.98186547e-01,

7.96640075e-04, 2.52947905e-03, 2.21160411e-02, 2.67231079e+00,

5.14794085e-08, 6.77497582e-05, 1.13131751e-04, 6.26424531e-05])

The first set of results is

[-0.54016972 0.54049209 -1.40646494 -0.73719452 -0.74496715 2.83032182

-0.87933836 -0.65211419 -0.13288216 -1.10391221 0.11377512 -2.37603465

-1.35245841 1.34875231 -0.94662911 -0.87763284 0.47554452 0.25084

-0.79472331 -1.84704125]

The first set of results has median

-0.741 (95% CI: -2.125, 2.127)

This is a have-your-cake-and-eat-it-too situation: the first set of results is correctly labeled (sim.results['y = N^1']), but you can easily access it without having to type all that (sim.results[0]).

The objdict#

When you’re just writing throwaway analysis code, it can be a pain to type mydict['key1']['key2'] over and over. (Right-pinky overuse is a real medical issue.) Wouldn’t it be nice if you could just type mydict.key1.key2, but otherwise have everything work exactly like a dict? This is where the objdict comes in: it’s identical to an odict (and hence like a regular dict), except you can use “object syntax” (a.b)

instead of “dict syntax” (a['b']). This is especially handy for using f-strings, since you don’t have to worry about nested quotes:

[7]:

ob = sc.objdict(key1=['some', 'strings'], key2=[1,2,3])

print(f'Checking {ob[0] = }')

print(f'Checking {ob.key1 = }')

print(f'Checking {ob["key1"] = }') # We need to use double-quotes inside since single quotes are taken!

Checking ob[0] = ['some', 'strings']

Checking ob.key1 = ['some', 'strings']

Checking ob["key1"] = ['some', 'strings']

In most cases, you probably want to use objdicts rather than odicts just to have the extra flexibility. Why would you ever use an odict over an objdict? Mostly just because there’s small but nonzero overhead in doing the extra attribute checking: odict is faster (faster than even collections.OrderedDict, though slower than a plain dict). The differences are tiny (literally nanoseconds) so won’t matter unless you’re doing millions of operations. But if you’re

reading this, chances are high that you do sometimes need to do millions of dict operations.

Dataframes#

The Sciris sc.dataframe() works exactly like pandas pd.DataFrame(), with a couple extra features, mostly to do with creation, indexing, and manipulation.

Dataframe creation#

Any valid pandas dataframe initialization works exactly the same in Sciris. However, Sciris is a bit more flexible about how you can create the dataframe, again optimized for letting you make them quickly with minimal code. For example:

[8]:

import pandas as pd

x = ['a','b','c']

y = [1, 2, 3]

z = [1, 0, 1]

df = pd.DataFrame(dict(x=x, y=y, z=z)) # Pandas

df = sc.dataframe(x=x, y=y, z=z) # Sciris

It’s not a huge difference, but the Sciris one is shorter. Sciris also makes it easier to define types on dataframe creation:

[9]:

df = sc.dataframe(x=x, y=y, z=z, dtypes=[str, float, bool])

print(df)

x y z

0 a 1.0 True

1 b 2.0 False

2 c 3.0 True

You can also define data types along with the columns:

[10]:

columns = dict(x=str, y=float, z=bool)

data = [

['a', 1, 1],

['b', 2, 0],

['c', 3, 1],

]

df = sc.dataframe(columns=columns, data=data)

df.disp()

x y z

0 a 1.0 True

1 b 2.0 False

2 c 3.0 True

The df.disp() command will do its best to show the full dataframe. By default, Sciris dataframes (just like pandas) are shown in abbreviated form:

[11]:

df = sc.dataframe(data=np.random.rand(70,10))

print(df)

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 \

0 0.068829 0.241926 0.682636 0.881461 0.169705 0.692593 0.380404

1 0.248104 0.780141 0.718935 0.791855 0.748851 0.487138 0.074483

2 0.518904 0.683791 0.287663 0.707347 0.853853 0.668351 0.132939

3 0.984054 0.259648 0.255607 0.078166 0.617954 0.855227 0.754584

4 0.341654 0.081161 0.150890 0.697708 0.029461 0.793399 0.191758

.. ... ... ... ... ... ... ...

65 0.287400 0.530047 0.868400 0.777354 0.465318 0.899153 0.084952

66 0.121803 0.073402 0.869759 0.009655 0.186355 0.722959 0.497785

67 0.972743 0.533272 0.432389 0.534526 0.823315 0.947444 0.510858

68 0.719464 0.754241 0.800823 0.099966 0.246951 0.783649 0.433527

69 0.856336 0.800341 0.856466 0.857087 0.470238 0.238030 0.153689

7 8 9

0 0.243757 0.304405 0.545881

1 0.505455 0.247395 0.513261

2 0.292416 0.051455 0.710364

3 0.688046 0.255058 0.567092

4 0.867201 0.392203 0.477744

.. ... ... ...

65 0.690331 0.074770 0.647247

66 0.687649 0.213036 0.625880

67 0.912658 0.731800 0.934272

68 0.219143 0.000124 0.061581

69 0.059932 0.916551 0.338985

[70 rows x 10 columns]

But sometimes you just want to see the whole thing. The official way to do it in pandas is with pd.options_context, but this is a lot of effort if you’re just poking around in a script or terminal (which, if you’re printing a dataframe, you probably are). By default, df.disp() shows the whole damn thing:

[12]:

df.disp()

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

0 0.0688 0.2419 0.6826 0.8815 0.1697 0.6926 0.3804 0.2438 0.3044 0.5459

1 0.2481 0.7801 0.7189 0.7919 0.7489 0.4871 0.0745 0.5055 0.2474 0.5133

2 0.5189 0.6838 0.2877 0.7073 0.8539 0.6684 0.1329 0.2924 0.0515 0.7104

3 0.9841 0.2596 0.2556 0.0782 0.6180 0.8552 0.7546 0.6880 0.2551 0.5671

4 0.3417 0.0812 0.1509 0.6977 0.0295 0.7934 0.1918 0.8672 0.3922 0.4777

5 0.3446 0.7548 0.5690 0.3887 0.8617 0.5396 0.8991 0.6139 0.7869 0.8014

6 0.9610 0.7713 0.0052 0.3632 0.5823 0.4254 0.0710 0.1985 0.9791 0.8879

7 0.7300 0.2108 0.2462 0.9431 0.4787 0.0296 0.2279 0.6451 0.6524 0.0599

8 0.5914 0.8808 0.1240 0.9635 0.7500 0.1953 0.5162 0.6061 0.7892 0.5430

9 0.8725 0.0475 0.4655 0.1811 0.6285 0.1263 0.4667 0.7709 0.7521 0.0140

10 0.2478 0.2674 0.0546 0.3918 0.9033 0.5426 0.8303 0.0789 0.1589 0.1681

11 0.6500 0.3115 0.6682 0.2405 0.7116 0.2016 0.6633 0.5882 0.4821 0.6737

12 0.1827 0.1417 0.7272 0.8353 0.1033 0.2786 0.5160 0.5508 0.0655 0.3077

13 0.2035 0.9075 0.5474 0.7481 0.4970 0.9446 0.3011 0.3672 0.8236 0.3308

14 0.1145 0.8153 0.7400 0.9226 0.3878 0.0397 0.9604 0.4536 0.6970 0.1307

15 0.9345 0.2955 0.2890 0.6552 0.5069 0.9101 0.8020 0.1375 0.5055 0.1282

16 0.2508 0.6016 0.8613 0.8011 0.0106 0.1232 0.2061 0.9371 0.6674 0.3908

17 0.6847 0.8129 0.2201 0.2736 0.8626 0.7855 0.5447 0.2472 0.2908 0.9982

18 0.2125 0.1723 0.2516 0.8522 0.9286 0.6729 0.7500 0.0694 0.4912 0.7800

19 0.1246 0.1820 0.2288 0.2676 0.5196 0.1966 0.8938 0.9926 0.4833 0.8006

20 0.2539 0.8957 0.1875 0.4169 0.5024 0.7749 0.8566 0.3410 0.1210 0.4529

21 0.9511 0.2473 0.8047 0.9847 0.6583 0.4827 0.5275 0.7395 0.1190 0.1450

22 0.3049 0.2177 0.7142 0.4809 0.9941 0.2988 0.6830 0.1933 0.2663 0.0522

23 0.5462 0.4258 0.8021 0.9475 0.9271 0.9405 0.3673 0.9466 0.9162 0.0894

24 0.1176 0.5949 0.9471 0.1546 0.9394 0.1604 0.8790 0.8536 0.6946 0.1694

25 0.6818 0.9369 0.4188 0.4812 0.2541 0.7793 0.9329 0.9316 0.8520 0.2918

26 0.4045 0.6754 0.7968 0.3600 0.6089 0.0587 0.0246 0.9297 0.3781 0.7141

27 0.1728 0.4030 0.5822 0.8054 0.2649 0.9627 0.1023 0.7473 0.3939 0.9048

28 0.3638 0.3582 0.7914 0.6361 0.3271 0.5739 0.2361 0.2690 0.5097 0.1470

29 0.0416 0.5909 0.3645 0.1136 0.7435 0.6902 0.1362 0.5343 0.3330 0.3016

30 0.4766 0.8512 0.9706 0.8876 0.2547 0.0289 0.0397 0.9713 0.4744 0.3383

31 0.1613 0.4683 0.5405 0.6570 0.2270 0.2051 0.4478 0.1183 0.4998 0.9388

32 0.9060 0.7229 0.0421 0.3559 0.3631 0.1381 0.3900 0.7697 0.0610 0.7826

33 0.7877 0.4545 0.3434 0.3541 0.1322 0.2254 0.6850 0.2553 0.1322 0.6040

34 0.1953 0.5863 0.3579 0.9078 0.1122 0.3918 0.2104 0.4307 0.4514 0.1508

35 0.4782 0.8472 0.0019 0.6280 0.4576 0.6448 0.6920 0.2695 0.6703 0.3597

36 0.4026 0.8658 0.2599 0.9754 0.4449 0.9216 0.9235 0.7847 0.2513 0.8303

37 0.3907 0.4061 0.4413 0.6886 0.0100 0.4628 0.9032 0.7428 0.5912 0.8380

38 0.0288 0.2822 0.2435 0.7993 0.0838 0.4658 0.8373 0.9531 0.8186 0.2171

39 0.5674 0.5217 0.0611 0.5889 0.3574 0.4113 0.2085 0.6188 0.4565 0.8834

40 0.8627 0.5539 0.0616 0.3374 0.8617 0.0440 0.9283 0.6527 0.1154 0.3695

41 0.6180 0.8868 0.0093 0.8453 0.7134 0.8029 0.8075 0.9344 0.3582 0.0642

42 0.3415 0.4411 0.0952 0.2280 0.9467 0.6402 0.7704 0.2491 0.1224 0.8246

43 0.0038 0.8099 0.2127 0.9253 0.6545 0.2960 0.8862 0.6199 0.4815 0.8786

44 0.4773 0.0309 0.8233 0.1599 0.4644 0.6569 0.3903 0.8771 0.5275 0.2151

45 0.5052 0.4759 0.8976 0.2452 0.8920 0.9158 0.6642 0.4116 0.4561 0.1146

46 0.7042 0.3309 0.3871 0.5703 0.5064 0.1761 0.1945 0.1771 0.1294 0.1412

47 0.7374 0.7482 0.5953 0.7103 0.7889 0.5241 0.0049 0.3054 0.9225 0.8611

48 0.3578 0.4525 0.0622 0.2354 0.1427 0.6407 0.4946 0.7127 0.8434 0.7161

49 0.2164 0.5784 0.2846 0.0209 0.1487 0.8037 0.8088 0.9023 0.1076 0.9531

50 0.9659 0.9114 0.3567 0.6589 0.7454 0.3466 0.6390 0.9471 0.9515 0.8990

51 0.1144 0.9875 0.2862 0.3171 0.2284 0.5542 0.6006 0.0338 0.4961 0.8604

52 0.6379 0.7656 0.8104 0.8420 0.5057 0.0326 0.0436 0.2195 0.7790 0.3235

53 0.0293 0.3355 0.4341 0.1196 0.2086 0.1097 0.9650 0.0960 0.0220 0.8998

54 0.4761 0.6993 0.2631 0.9201 0.6151 0.3940 0.1397 0.7004 0.3467 0.1893

55 0.0789 0.0482 0.6698 0.4154 0.7079 0.8237 0.2328 0.8455 0.5686 0.4393

56 0.2845 0.3639 0.7660 0.8642 0.4647 0.2381 0.6505 0.9743 0.3807 0.0584

57 0.0188 0.4740 0.3770 0.2315 0.8721 0.6522 0.0615 0.5997 0.6090 0.3211

58 0.9146 0.1521 0.0843 0.7329 0.1864 0.6070 0.7472 0.2426 0.8733 0.9534

59 0.7767 0.6267 0.5570 0.4073 0.7933 0.1704 0.9963 0.6588 0.5234 0.1957

60 0.6101 0.3103 0.7323 0.3271 0.6262 0.3373 0.1567 0.2305 0.7151 0.2405

61 0.5336 0.3304 0.5324 0.9642 0.2002 0.5748 0.9263 0.8270 0.5639 0.8276

62 0.4606 0.3458 0.9793 0.6902 0.7007 0.4193 0.7739 0.6563 0.0632 0.5321

63 0.7706 0.1433 0.5348 0.3519 0.4583 0.2515 0.3233 0.9482 0.7797 0.4473

64 0.1789 0.3919 0.5088 0.6881 0.7114 0.1602 0.6840 0.1926 0.0170 0.8583

65 0.2874 0.5300 0.8684 0.7774 0.4653 0.8992 0.0850 0.6903 0.0748 0.6472

66 0.1218 0.0734 0.8698 0.0097 0.1864 0.7230 0.4978 0.6876 0.2130 0.6259

67 0.9727 0.5333 0.4324 0.5345 0.8233 0.9474 0.5109 0.9127 0.7318 0.9343

68 0.7195 0.7542 0.8008 0.1000 0.2470 0.7836 0.4335 0.2191 0.0001 0.0616

69 0.8563 0.8003 0.8565 0.8571 0.4702 0.2380 0.1537 0.0599 0.9166 0.3390

You can also pass other options if you want to customize it further:

[13]:

df.disp(precision=1, ncols=5, nrows=10, colheader_justify='left')

0 1 ... 8 9

0 6.9e-02 2.4e-01 ... 3.0e-01 5.5e-01

1 2.5e-01 7.8e-01 ... 2.5e-01 5.1e-01

2 5.2e-01 6.8e-01 ... 5.1e-02 7.1e-01

3 9.8e-01 2.6e-01 ... 2.6e-01 5.7e-01

4 3.4e-01 8.1e-02 ... 3.9e-01 4.8e-01

.. ... ... ... ... ...

65 2.9e-01 5.3e-01 ... 7.5e-02 6.5e-01

66 1.2e-01 7.3e-02 ... 2.1e-01 6.3e-01

67 9.7e-01 5.3e-01 ... 7.3e-01 9.3e-01

68 7.2e-01 7.5e-01 ... 1.2e-04 6.2e-02

69 8.6e-01 8.0e-01 ... 9.2e-01 3.4e-01

[70 rows x 10 columns]

Dataframe indexing#

All the regular pandas methods (df['mycol'], df.mycol, df.loc, df.iloc, etc.) work exactly the same. But Sciris gives additional options for indexing. Specifically, getitem commands (what happens under the hood when you call df[thing]) will first try the standard pandas getitem, but then fall back to iloc if that fails. For example:

[14]:

df = sc.dataframe(

x = [1, 2, 3],

values = [45, 23, 37],

valid = [1, 0, 1]

)

sc.heading('Regular pandas indexing')

print(df['values',1])

sc.heading('Pandas-like iloc indexing')

print(df.iloc[1])

sc.heading('Automatic iloc indexing')

print(df[1]) # Would be a KeyError in regular pandas

———————————————————————

Regular pandas indexing

———————————————————————

23

—————————————————————————

Pandas-like iloc indexing

—————————————————————————

x 2

values 23

valid 0

Name: 1, dtype: int64

———————————————————————

Automatic iloc indexing

———————————————————————

x 2

values 23

valid 0

Name: 1, dtype: int64

Dataframe manipulation#

One quirk of pandas dataframes is that almost every operation creates a copy rather than modifies the original dataframe in-place (leading to the infamous SettingWithCopyWarning.) This is extremely helpful, and yet, sometimes you do want to modify a dataframe in place. For example, to append a row:

[15]:

# Create the dataframe

df = sc.dataframe(

x = ['a','b','c'],

y = [1, 2, 3],

z = [1, 0, 1],

)

# Define the new row

newrow = ['d', 4, 0]

# Append it in-place

df.appendrow(newrow)

# Show the result

print(df)

x y z

0 a 1 1

1 b 2 0

2 c 3 1

3 d 4 0

That was easy! For reference, here’s the pandas equivalent (since append was deprecated):

[16]:

# Convert to a vanilla dataframe

pdf = df.to_pandas()

# Define the new row

newrow = ['e', 5, 1]

# Append it

pdf = pd.concat([pdf, pd.DataFrame([newrow], columns=pdf.columns)])

That’s rather a pain to type, and if you mess up (e.g. type newrow instead of [newrow]), in some cases it won’t even fail, just give you the wrong result! Crikey.

Just like how sc.cat() will take anything vaguely arrayish and turn it into an actual array, sc.dataframe.cat() will do the same thing:

[17]:

df = sc.dataframe.cat(

sc.dataframe(x=['a','b'], y=[1,2]), # Actual dataframe

dict(x=['c','d'], y=[3,4]), # Dict of data

[['e',5], ['f', 6]], # Or just the data!

)

print(df)

x y

0 a 1

1 b 2

2 c d

3 3 4

4 e 5

5 f 6