Advanced features#

Here are yet more tools that the average user won’t need, but might come in handy one day.

Click here to open an interactive version of this notebook.

Nested dictionaries#

Nested dictionaries are a useful way of storing complex data (and in fact are more or less the basis of JSON), but can be a pain to interact with if you don’t know the structure in advance. Sciris has several functions for working with nested dictionaries. For example:

[1]:

import sciris as sc

# Create the structure

nest = {}

sc.makenested(nest, ['key1','key1.1'])

sc.makenested(nest, ['key1','key1.2'])

sc.makenested(nest, ['key1','key1.3'])

sc.makenested(nest, ['key2','key2.1','key2.1.1'])

sc.makenested(nest, ['key2','key2.2','key2.2.1'])

# Set the value for each "twig"

count = 0

for twig in sc.iternested(nest):

count += 1

sc.setnested(nest, twig, count)

# Convert to a JSON to view the structure more clearly

sc.printjson(nest)

# Get all the values from the dict

values = []

for twig in sc.iternested(nest):

values.append(sc.getnested(nest, twig))

print(f'{values = }')

{

"key1": {

"key1.1": 1,

"key1.2": 2,

"key1.3": 3

},

"key2": {

"key2.1": {

"key2.1.1": 4

},

"key2.2": {

"key2.2.1": 5

}

}

}

values = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

Sciris also has a sc.search() function, which can find either keys or values that match a certain pattern:

[2]:

print(sc.search(nest, 'key2.1.1'))

print(sc.search(nest, value=5))

[['key2', 'key2.1', 'key2.1.1']]

[['key2', 'key2.2', 'key2.2.1']]

There’s even an sc.iterobj() function that can make arbitrary changes to an object:

[3]:

def increment(obj):

return obj + 1000 if isinstance(obj, int) and obj !=3 else obj

sc.iterobj(nest, increment, inplace=True)

sc.printjson(nest)

{

"key1": {

"key1.1": 1001,

"key1.2": 1002,

"key1.3": 3

},

"key2": {

"key2.1": {

"key2.1.1": 1004

},

"key2.2": {

"key2.2.1": 1005

}

}

}

Context blocks#

Sciris contains two context block (i.e. “with ... as”) classes for catching what happens inside them.

sc.capture() captures all text output to a variable:

[4]:

import sciris as sc

import numpy as np

def verbose_func(n=200):

for i in range(n):

print(f'Here are 5 random numbers: {np.random.rand(5)}')

with sc.capture() as text:

verbose_func()

lines = text.splitlines()

target = '777'

for l,line in enumerate(lines):

if target in line:

print(f'Found target {target} on line {l}: {line}')

Found target 777 on line 37: Here are 5 random numbers: [0.23091441 0.92720101 0.64386704 0.98108182 0.77739743]

Found target 777 on line 40: Here are 5 random numbers: [0.10017502 0.85447773 0.70585521 0.79761481 0.56303318]

Found target 777 on line 42: Here are 5 random numbers: [0.98338691 0.23776133 0.79377702 0.38521457 0.13102052]

Found target 777 on line 57: Here are 5 random numbers: [0.48547204 0.0794115 0.83758695 0.59309727 0.48170777]

Found target 777 on line 128: Here are 5 random numbers: [0.91227649 0.17771961 0.64710676 0.36414018 0.0829745 ]

The other function, sc.tryexcept(), is a more compact way of writing try ... except blocks, and gives detailed control of error handling:

[5]:

def fickle_func(n=1):

for i in range(n):

rnd = np.random.rand()

if rnd < 0.005:

raise ValueError(f'Value {rnd:n} too small')

elif rnd > 0.99:

raise RuntimeError(f'Value {rnd:n} too big')

sc.heading('Simple usage, exit gracefully at first exception')

with sc.tryexcept():

fickle_func(n=1000)

sc.heading('Store all history')

tryexc = None

for i in range(1000):

with sc.tryexcept(history=tryexc, verbose=False) as tryexc:

fickle_func()

tryexc.disp()

————————————————————————————————————————————————

Simple usage, exit gracefully at first exception

————————————————————————————————————————————————

<class 'RuntimeError'> Value 0.995604 too big

—————————————————

Store all history

—————————————————

type value traceback

0 <class 'RuntimeError'> Value 0.992427 too big <traceback object at 0x7f3430157a80>

1 <class 'ValueError'> Value 0.0035279 too small <traceback object at 0x7f3428df4a80>

2 <class 'RuntimeError'> Value 0.991026 too big <traceback object at 0x7f3402fa3a80>

3 <class 'RuntimeError'> Value 0.996673 too big <traceback object at 0x7f3402eb74c0>

4 <class 'ValueError'> Value 0.000397334 too small <traceback object at 0x7f3402eb7400>

5 <class 'RuntimeError'> Value 0.992735 too big <traceback object at 0x7f3402eb7140>

6 <class 'RuntimeError'> Value 0.995062 too big <traceback object at 0x7f3402eb76c0>

7 <class 'RuntimeError'> Value 0.992525 too big <traceback object at 0x7f3402eb7540>

8 <class 'RuntimeError'> Value 0.993638 too big <traceback object at 0x7f3402eb6f00>

9 <class 'ValueError'> Value 0.001585 too small <traceback object at 0x7f3402eb7800>

10 <class 'ValueError'> Value 0.00207436 too small <traceback object at 0x7f3402eb7300>

11 <class 'RuntimeError'> Value 0.996381 too big <traceback object at 0x7f3402eb7880>

Interpolation and optimization#

Sciris includes two algorithms that complement their SciPy relatives: interpolation and optimization.

Interpolation#

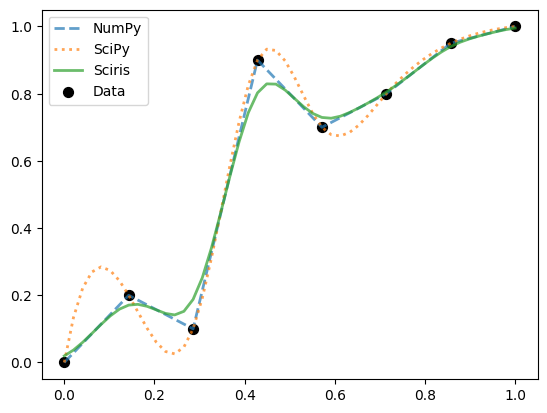

The function sc.smoothinterp() smoothly interpolates between points but does not use spline interpolation; this makes it somewhat of a balance between numpy.interp() (which only interpolates linearly) and scipy.interpolate.interp1d(..., method='cubic'), which takes considerable liberties between data points:

[6]:

import sciris as sc

import numpy as np

import pylab as pl

from scipy import interpolate

# Create the data

origy = np.array([0, 0.2, 0.1, 0.9, 0.7, 0.8, 0.95, 1])

origx = np.linspace(0, 1, len(origy))

newx = np.linspace(0, 1)

# Create the interpolations

sc_y = sc.smoothinterp(newx, origx, origy, smoothness=5)

np_y = np.interp(newx, origx, origy)

si_y = interpolate.interp1d(origx, origy, 'cubic')(newx)

# Plot

kw = dict(lw=2, alpha=0.7)

pl.plot(newx, np_y, '--', label='NumPy', **kw)

pl.plot(newx, si_y, ':', label='SciPy', **kw)

pl.plot(newx, sc_y, '-', label='Sciris', **kw)

pl.scatter(origx, origy, s=50, c='k', label='Data')

pl.legend();

As you can see, sc.smoothinterp() gives a more “reasonable” approximation to the data, at the expense of not exactly passing through all the data points.

Optimization#

Sciris includes a gradient descent optimization method, adaptive stochastic descent (ASD), that can outperform SciPy’s built-in optimization methods (such as simplex) for certain types of optimization problem. For example:

[7]:

# Basic usage

import numpy as np

import sciris as sc

from scipy import optimize

# Very simple optimization problem -- set all numbers to 0

func = np.linalg.norm

x = [1, 2, 3]

with sc.timer('scipy.optimize()'):

opt_scipy = optimize.minimize(func, x)

with sc.timer('sciris.asd()'):

opt_sciris = sc.asd(func, x, verbose=False)

print(f'Scipy result: {func(opt_scipy.x)}')

print(f'Sciris result: {func(opt_sciris.x)}')

scipy.optimize(): 21.5 ms

sciris.asd(): 5.48 ms

Scipy result: 4.829290232718364e-08

Sciris result: 2.9796874070320123e-16

Compared to SciPy’s simplex algorithm, Sciris’ ASD algorithm was ≈3 times faster and found a result ≈8 orders of magnitude smaller.

Animation#

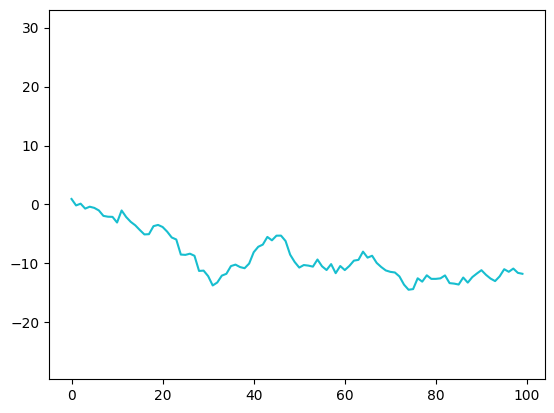

And finally, let’s end on something fun. Sciris has an sc.animation() class with lots of options, but you can also just make a quick movie from a series of plots. For example, let’s make some lines dance:

[8]:

pl.figure()

frames = [pl.plot(pl.cumsum(pl.randn(100))) for i in range(20)] # Create frames

sc.savemovie(frames, 'dancing_lines.gif'); # Save movie as a gif

Saving 20 frames at 10.0 fps and 150 dpi to "dancing_lines.gif" using imagemagick...

Done; movie saved to "dancing_lines.gif"

File size: 127 KB

Elapsed time: 5.50 s

This creates the following movie, which is a rather delightful way to end:

We hope you enjoyed this series of tutorials! Remember, write to us if you want to get in touch.